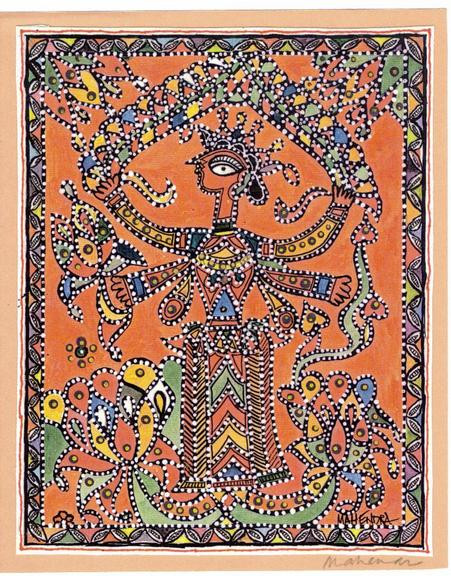

[The above painting is done by famous artist and cartoonist Mahendra Shah.]

[The History of Mithila Paintings is provided by Dr. Kailash K. Mishra. Dr. Kailash Kumar Mishra is an anthropologist who works as free lance scholar and looks after the Bahudha Utkarsh Foundation as its founder and Managing Trustee. he can be contacted at kailashkmishra@gmail.com This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it , Ph: 09868963743]

Like the diversity of India, its folk art also presents a huge canvas and depicts the cultural mosaics of this country in a very colourful style. This art can rightly be termed as an ocean of the folk art6, which, since earliest times, has been fed by the rivers of popular artistic creativity – rivers that have flowed into it from all cultural-geographical pockets of the Indian sub-continent. The well-known grammarian, Panini, drew a distinction between artists – the rajashilpi, or craftsman employed by the court – and the gramashilpi, or village craftsman (Mookerjee R.K. 1962:16).7Originally shilpin would seem to have been a term generally applied to the technically trained craftsman; later, however, it came to denote the artisan (Puri, B.N. 1968:217)8.

Thus the writing concerning the theory of art are referred to collectively as the shilpashastras (Kramrisch, S 1946:9).9 Being for the most part of a highly schematic character, these manuals of artistic instruction could not, of course, be expected to include a description of folk art or of amateur art practised by women at home. By and large they form part of orthodox ecclesiastical literature with art as the handmaiden of the courts of Brahmanic orthodoxy (Coomaraswamy, A.K.1964: 33-34)10. But that did not cause any disturbance for the women and the commoners of India to practice various forms of creativity through various mediums on the occasion of rituals, altars, and festivals and also during the leisure period. The fellow villagers and locals always appreciated their creativity and innovation. As a result, in Sanskrit, as well as in the folk tradition, an artist is treated as a person with a magnetic ability to create a world of imagination. Metaphorically, an artist is always compared with the Gods. “In Hinduism, Vishnu has a thousand names, many of which refer to works of art. In Islam, one of the hundred names of Allah is Musawwer, the artist. The Sanskrit word kala (art) means the divine attributes which direct human acts and thoughts. Man, God and art are inseparable. Art is not removed from everyday life, it reflects a world view (Saraswati Baidyanath 1999:10)11 No distinction is made between fine and decorative, free or servile arts. The eighteen or more professional arts (silpa) and the sixty-four vocational arts (kala) embrace all kinds of skilled activity. There is no difference between a painter and a sculptor. Both are known as silpi or karigar. The term silpa designates ceremonial act in the Asvalayana Srautasutra, and in this sense it is close to karu, which in the Vedic context stands for a maker or an artist, a singer of hymns, or a poet. In a reference in the Rgveda, Visvakarma, a god of creation, is mentioned as dhatu-karmara, while karmara alone refers to artisans and artificers (Rgveda X.72.2; Atharveda III 5-6; Manu IV 215)12. Visvakarma is supposed to create things out of dhatu, “raw material”, an act known as sanghamana (Rgveda X 72.2)13. The process of cutting, shaping and painting has been often explained in the text by the taks14.

In Mithila a woman does painting on the wall, surface, movable objects, and canvas; makes images of gods, goddesses, animals and mythological characters from the lump of clay; prepares objects such as baskets, small containers, and play items from sikki grass; does embroidery on quilt – popularly known as kethari and sujani; sings varieties of ritual and work songs (Mishra, Kailash Kumar 2003)15. These artistic activities are done by a lady as a routine work that makes her a complete creative personality: a singer, a sculptor, a painter, an embroidery design maker and what not! Without knowing these primary details one may not understand the aesthetic wonder of Mithila paintings. From generation to generation the women of Mithila have produced a vigorous distinctive painting. That this traditional art has survived the innumerable vicissitudes of history is due, first of all, to the social organization of Mithila, one based on the village community, in whose corporate life the women have clearly understood roles. Beyond their extended families, the women artists work for a rural society with whose requirements they are perfectly acquainted. It is within this framework that the women continue to reproduce age-old forms; indeed countless recapitulations have resulted in an attitude of mind in which they can produce the most abstract designs without conscious effort. The possibility of any radical assertion of individuality in the modern sense is extremely limited (Mookerjee Ajit 1977: 7)16. This communal village life is strengthened and sustained by the universal prevalence of social gatherings, traditional storytelling, dancing and singing festivities and ceremonies, processions and rituals.

6 Lokakalasaritasagara.

7 Mookerjee, R.K. Notes on Early Indian Art, Allahabad, 1962.

8 Puri, B.N. India in the Time of Patanjali, Bombay, 1968.

9 Shilpanis as works of art in the Aitareya Brahmana, cf. Kramrisch, S The Hindu Temple, Calcutta, p.9, 1946.

10 From the English translation in Coomaraswamy, A.K., The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon, New York, 1964.

11 Saraswati, Baidyanath, VILLAGE INDIA: Identification and Enhancement of Cultural Heriatge – An Internal Necessity in the Management of Development (Interim Report), New Delhi, UNESCO Chair in the Field of Cultural Development; Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1999.

12 Rgveda, X.72.2; Atharveda, III, 5-6; Manu, IV. 215.

13 Rgveda X 72.2

14 Rgveda: rathakas who used wood for joining and making chariot, is called taksaka in the Maitrayani Samhita, IV. 3.8.

15 Mishra, Kailash Kumar “Mithila Painting: The Women’s Creativity”, in The Unshackled Spirti from Bihar (An Exhibition of Artists from Erstwhile Bihar), Patna, RHYTHM Centre for Art and Culture 2003.

16 Mookerjee Ajit In the Preface of Ve`quaud, Yves’ , Women Painters of Mithila, London, Thames and Hudson, 1977.